I keep tripping over the phrase “we immigrants” in Justine Strand de Oliveira’s substack post – “Echoes of 1975: another reason we immigrants don’t understand Portugal”.

It’s a thoughtful post about why “we immigrants” can never fully understand Portugal. It’s well-researched, touching on the complexity of 1975, that turbulent year after the Carnation Revolution when everything hung in the balance.

But: who exactly are “we immigrants”? And why does this title make me flinch?

I’m afraid that the phrase “we immigrants” used in this context performs a kind of epistemic move that is the mirror image of what Elísio Macamo, a Mozambican sociologist, describes in his article “Sobre a superioridade inocente de Portugal” (read in Público)

Where the Portuguese person in Macamo’s example assumes the position of well-intentioned educator (preventing genuine dialogue), Justine’s “we immigrants” here assumes the position of a humble learner who can never fully understand – but in doing so, is actually claiming a particular kind of authority: the authority to define what the immigrant experience is, and to speak for a collective that doesn’t exist as she imagines it.

It’s something about “performing innocent humility”. It’s like the acknowledgment of one’s outsider status becomes its own form of positioning. “I know I can never truly understand” becomes a way of claiming a particular kind of sophisticated awareness that risks avoiding the messier reality of actual negotiation and relationship-building over time.

I came here 35 years ago—born and brought up in Kenya but living in England—carrying my own Portuguese mythology. My imagination had been triggered by my scuba diving off sixteenth century Portuguese wrecks in Mombasa harbour, collecting artefacts for the local museum. I was tantalized by Gedi, the hastily abandoned coastal town where legend says everyone fled when the “short men of the sea” (the Portuguese) were sighted coming to shore. I had been stung by Portuguese men o’ war.

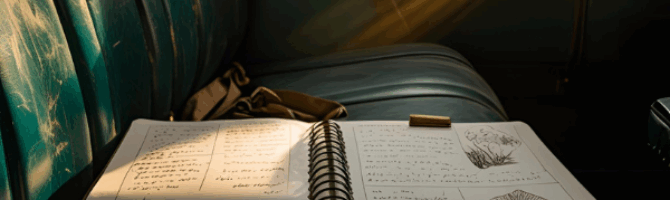

The ruins of Gedi in Kenya, shaping my imagination of the Portuguese in Portugal.

The ruins of Gedi in Kenya, shaping my imagination of the Portuguese in Portugal.

None of it was historically accurate. It was my Portugal before I got here.

The “real” Portugal was different. A windowless apartment in Carcavelos. Drinking water before bed because I couldn’t afford an alarm clock. Dancing at the sambódia every Sunday above the bombeiros. Learning Portuguese subjunctive from a Brazilian boyfriend whose complaints always started “Se fosse uma Brazileira…”

It was a different starting point from an American expat discovering the Carnation Revolution.

So my problem with “we immigrants” is that the framing treats belonging as binary – you either have access to the collective memory or you don’t – when my experience shows it is much more about the particular shape of your entanglement with the country. After 35 years, I’m not still waiting outside hoping to understand Portugal. I’ve built a life that is part of whatever Portugal is now, in my corner of it.

“We immigrants” isn’t a story about trying to grasp an elusive collective memory. It’s just… life. Piecing things together. Making mistakes. Building relationships. Watching Portugal change while you change too.

For all its good intentions, this is what I hear in the phrase “we immigrants”:

- A shared epistemological position (outsiders who can’t fully understand)

- A shared relationship to the host country (guests, learners, respectful observers)

- A shared class position (people with the leisure to read Faulkner, reflect on collective memory, exercise thoughtfulness)

- A shared national/cultural starting point (probably Western, probably anglophone)

And this is what it seems to obscure:

- The Nepali worker in construction who may never learn Portuguese

- The Brazilian who navigates a complex relationship of linguistic connection and social hierarchy

- The Syrian refugee who didn’t choose to be here

- The wealthy American retiree whose arrival is literally changing housing markets

- Me, with my 35-year relationship to this place and my own complex history with Portuguese imaginaries that predates my arrival

My experience is not about never being able to fully grasp Portugal’s collective memory – it’s about having constructed my own relationship to a place over decades, one that includes both understanding and non-understanding, belonging and non-belonging, in ways that are unique to my particular trajectory.

Translating from Portuguese:

- “Sobre a superioridade inocente de Portugal” – “About the innocent superiority of Portugal”

- “Se fosse uma Brazileira..” – If you were a Brazilian woman